Academics and researchers have put forth a number strategic frameworks that help us analyze companies and industries in a structured way. While most frameworks are useful, it is also important to understand their limitations in context of the industry being analyzed. A common framework used by most MBA-types (I was part of this bucket) is Porter's three generic strategies. However, few seem to realize the downsides of using this framework with respect to the technology industry.

Porter's Three Generic Strategies

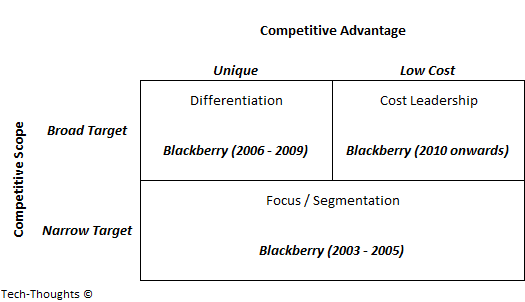

The figure at the top of this post gives a brief overview of Porter's three generic strategies. These strategies are based on two variables -- the competitive advantage that the company owns and the nature of the company's target market. These resulting "sustainable" strategies are as follows:

- If a firm is targeting customers in most or all segments of an industry based on offering the lowest price, it is following a cost leadership strategy;

- If it targets customers in most or all segments based on attributes other than price (e.g., via higher product quality or service) to command a higher price, it is pursuing a differentiation strategy. It is attempting to differentiate itself along these dimensions favorably relative to its competition. It seeks to minimize costs in areas that do not differentiate it, to remain cost competitive; or

- If it is focusing on one or a few segments, it is following a focus strategy. A firm may be attempting to offer a lower cost in that scope (cost focus) or differentiate itself in that scope (differentiation focus).

Let's use this framework with Blackberry to understand its pros and cons with respect to the technology industry.

A Brief History of Blackberry Smartphones

Blackberry launched the original smartphone, the 7230, in 2003. Over the next few years, Blackberry devices become popular among business users as "email access on the go" became a killer use case. With their focus on enterprise users, Blackberry clearly followed a "segmentation strategy" during this early phase.After 2005, Blackberry entered the mainstream consumer market with the launch of the Blackberry Pearl and the Blackberry Curve. Because of their superior communication services and keyboard, Blackberry's share of the US smartphone market continued to increase as the market expanded. As a result, Blackberry's market cap peaked in late-2008 (more than a year after the iPhone launch). In this phase, Blackberry clearly followed a "differentiation" strategy.

As the iPhone and Android smartphones began to make their mark, Blackberry began to feel pressured. As their sales declined, they proceeded to cut prices to cater to lower-end customers and those in emerging markets. Of course, the timing of strategy shifts may have differed by region.

The chart above shows the steep ASP decline seen by Blackberry devices from 2009 to 2011. Therefore, Blackberry transitioned to a "cost leadership" strategy around 2010 as they began their slide into irrelevance. Blackberry's position with respect to the three generic strategies is given in the figure below (the timelines are indicative and are not meant to be exact):

While the framework was quite useful in identifying Blackberry's strategy at each point in time, it gave us no indication as to what their long-term strategic position would be. This is because Porter's theories give a cross-sectional view of the industry, with no insight into industry evolution. None of the three generic strategies are truly "sustainable" in the technology industry because products, value chains, and consequently business models, evolve at an extremely rapid pace. In our Blackberry example, the company evolved from a new entrant to an industry leader to a cost leader and then faded into irrelevance in a span of ten years -- this is by no means an exception. This is in stark contrast to industries like apparel or automobiles where such changes could take decades or even longer. Comparing the evolution of consumer technology to such industries is a very common error among traditional analysts.

Of course, there are other aspects of Porter's work that are critical from the perspective of the technology industry -- the concept of tailored value chains, for example. I have written extensively about the value chain evolution framework which dovetails with this concept. But even the value chain evolution framework is not sufficient to understand the consumer technology space -- mainly because of what some describe as "irrational buyer behavior". This is where the identity-utility framework becomes crucial.